How drug repurposing opportunities are discovered

Drug repurposing uses scientific and computational approaches to unlock new value from existing medicines—bringing impactful, more affordable treatments to patients faster. Developing a new drug often takes more than a decade and can cost upwards of $1-2 billion. As a result, researchers are increasingly pursuing strategies that accelerate therapeutic development. One such strategy is drug repurposing: investigating whether a drug approved by a regulatory agency can also treat a different disease. By leveraging compounds with established safety, pharmacokinetic, and pharmacodynamic data, researchers can more efficiently explore new indications and translate discoveries into patient care. When these compounds are generic drugs, their affordability and accessibility provide additional benefits to patients and healthcare systems.

Advances in molecular biology, clinical informatics, and computational methods now allow researchers to systematically identify existing drugs that may act on new disease targets. In some cases, the new application requires adjustments to the dose, formulation, or route of administration to achieve the desired therapeutic effect, reflecting differences in pharmacokinetics, target tissues, or safety profiles.

So, how are repurposing opportunities identified in the first place? Researchers use a multidisciplinary process that combines mechanism-based hypothesis generation, insights from clinical observation, and experimental and computational screening. At Reboot Rx, we apply AI to systematically assess large numbers of potential repurposing opportunities for generic drugs and prioritize those with the strongest potential.

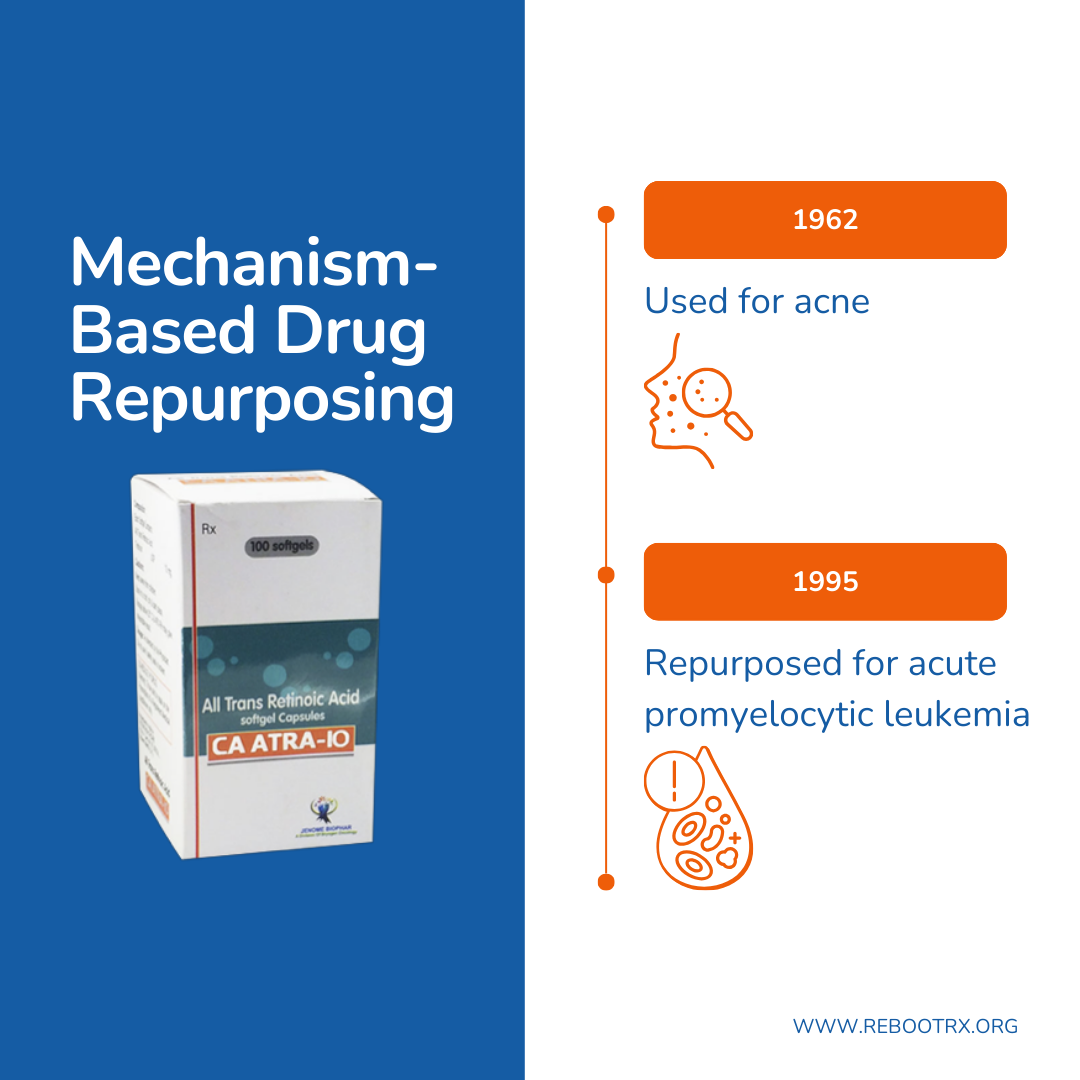

Mechanism-based drug repurposing

Some of the most compelling successes in drug repurposing have emerged from rational, mechanism-based approaches. These strategies rely on a deep understanding of disease pathophysiology and drug pharmacology to identify novel therapeutic applications based on shared or overlapping molecular pathways.

An example is all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA), a vitamin A derivative introduced for acne in 1962. In acne, ATRA binds normal Retinoic Acid Receptors (RARs) in skin cells to promote cell turnover and reduce lesions. In acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL), however, a genetic rearrangement fuses the promyelocytic leukemia (PML) and RARα genes to create an abnormal fusion protein, PML-RARα, which acts as a pathological receptor that blocks immature white blood cells (promyelocytes) from maturing properly. While ATRA targets the same receptor family in both diseases, the receptor context is different: in APL, binding the fusion receptor alters its function and releases the differentiation block, allowing leukemic cells to mature and die naturally. By connecting the drug’s molecular mechanism to the specific disease biology, researchers successfully repurposed ATRA, leading to FDA approval in 1995 and transforming APL into one of the most curable leukemias.

Mechanism-based repurposing has been further enabled by advances in genomics, proteomics, transcriptomics, and systems pharmacology, which provide increasingly detailed maps of disease biology and drug-target interactions. These technologies facilitate the identification of mechanistic overlaps between diseases and known compounds, opening new avenues for therapeutic innovation.

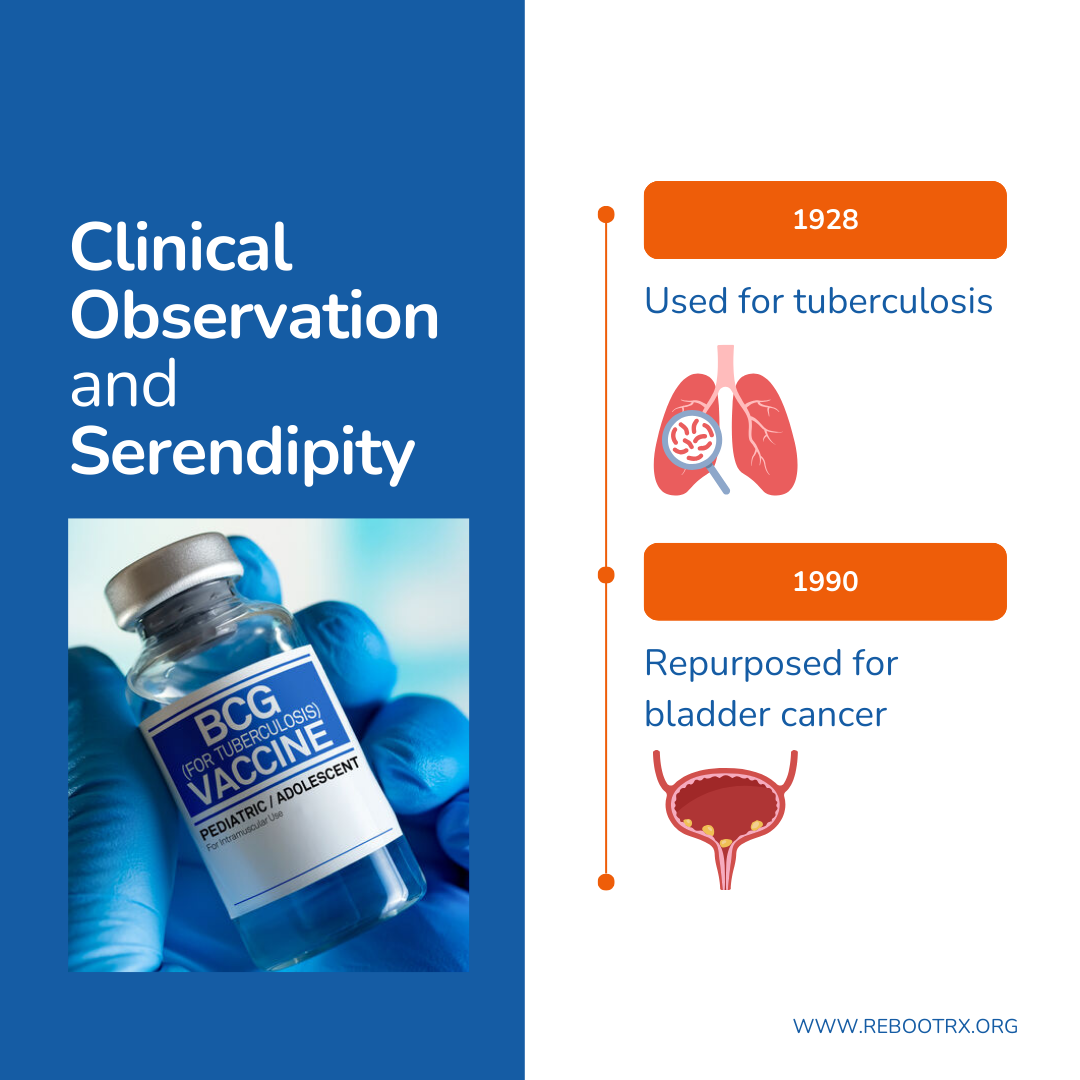

Clinical observation and serendipity

Mechanism-based approaches represent just one path to repurposing; equally important are insights gained directly from clinical practice or unexpected observations. Historically, attentive observation of patients receiving a drug for its approved indication has revealed unanticipated therapeutic effects for different conditions, and in some cases, serendipity has led to major breakthroughs in treatment.

A notable example is Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG), introduced for clinical use as a tuberculosis vaccine in 1928. Early evidence for BCG’s anti-cancer potential came from observational studies and autopsies, which noted that patients who had tuberculosis infections appeared to have a lower incidence of bladder cancer. Building on these observations, researchers hypothesized that BCG could stimulate the immune system to target tumor cells. Subsequent clinical studies confirmed that administering BCG intravesically elicits a localized immune response in the bladder, recruiting immune cells to attack malignant cells and reduce recurrence rates. BCG was first administered to patients with non-muscle invasive bladder cancer in 1977 and ultimately led to the FDA approval of BCG for non-muscle invasive bladder cancer in 1990. Today, it remains one of the earliest FDA-approved cancer immunotherapies and a cornerstone of first-line therapy.

Building on insights from individual clinical observations, today’s widespread electronic health records (EHRs) and real-world data (RWD) enable structured observational discovery at scale. Retrospective analyses of patient cohorts, off-label prescribing trends, and pharmacovigilance databases can reveal promising signals that may warrant mechanistic follow-up or clinical investigation. By integrating these data science tools into healthcare systems, clinicians are now better equipped than ever to identify, validate, and translate repurposing opportunities that arise from routine patient care.

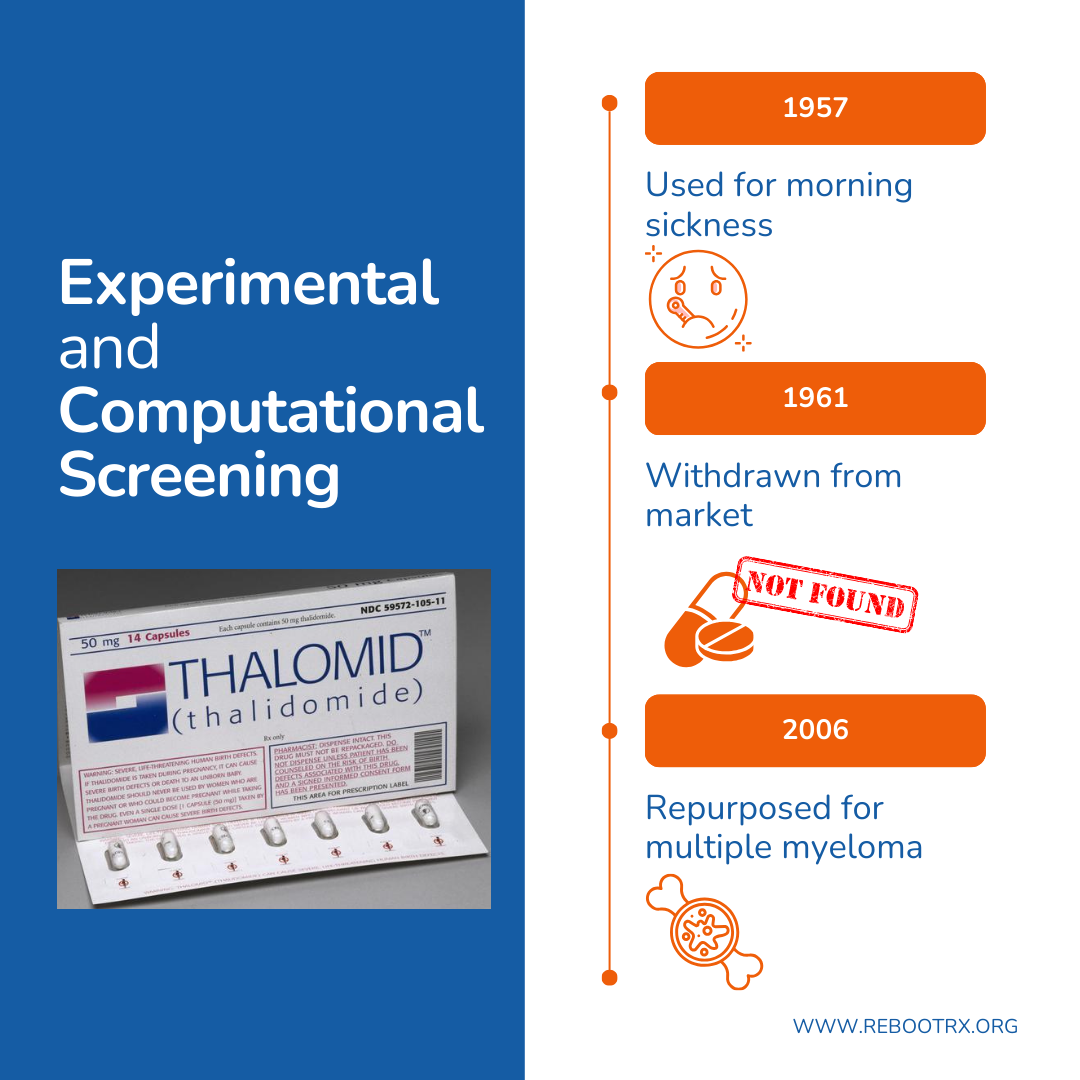

Experimental and computational screening

Complementing both mechanism-based and data-driven observational approaches, systematic screening using high-throughput experimental platforms or computational algorithms allows researchers to evaluate large numbers of drugs against diverse disease models.

An example is thalidomide, initially introduced in the 1950s as a sedative and treatment for morning sickness. The drug was withdrawn in 1961 after it was linked to widespread, severe birth defects. Decades later, early experimental screening using phenotypic assays revealed that thalidomide’s biological activities could be leveraged therapeutically in oncology. These studies showed that thalidomide inhibits tumor-associated angiogenesis and modulates immune activity in multiple myeloma, a cancer that depends heavily on both angiogenesis and immune interactions within the bone marrow. These effects led to FDA approval in 2006 and established thalidomide as a mainstay of cancer therapy.

Modern computational approaches to repurposing leverage machine learning, network-based analysis, and transcriptomic profiling to identify drugs that may reverse disease-associated gene expression patterns or target key nodes in disease-specific pathways. These in silico predictions may be evaluated or further tested using phenotypic screening, functional genomics, or patient-derived models to assess therapeutic potential.

These scalable tools are increasingly capable of uncovering novel applications not only for widely used drugs but also for previously shelved compounds, rescuing clinical value from agents once considered nonviable.

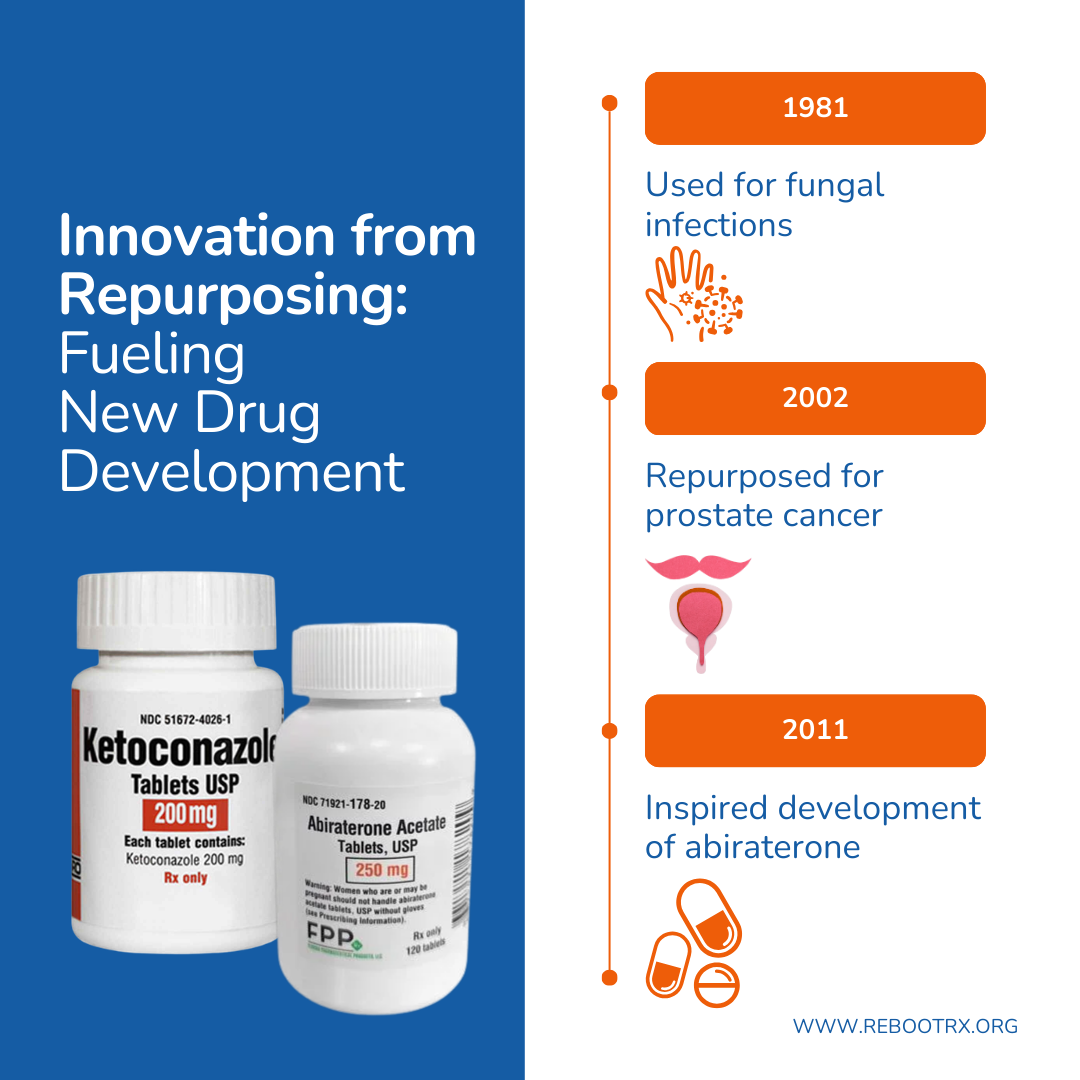

Innovation from repurposing: fueling new drug development

While many repurposing efforts aim to find new uses for existing drugs, these discoveries can also inspire the development of entirely new therapies. A notable example is ketoconazole, originally approved by the FDA in 1981 as an antifungal agent. Clinicians observed that men treated for fungal infections sometimes developed breast enlargement, a clue to the drug’s hormonal activity. This led to the hypothesis that ketoconazole blocks testosterone synthesis, a mechanism implicated in the androgen signaling pathway that drives prostate cancer. Subsequent clinical trials demonstrated its effectiveness in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer, where patients take higher doses over a longer duration than for antifungal therapy. Although ketoconazole was never formally FDA-approved for prostate cancer, by 2002 it was widely used off-label in clinical practice.

Ketoconazole’s inhibition of the CYP17 enzyme revealed how blocking androgen synthesis could slow tumor growth. This insight led to the development of abiraterone, a more selective and better-tolerated drug, approved by the FDA in 2011, that largely replaced ketoconazole. Now off-patent, abiraterone itself may one day be explored for additional generic drug repurposing opportunities. This example illustrates how repurposing not only advances current therapies but also generates new candidates for drug development.

The future of drug repurposing

Drug repurposing is entering a new era, driven by unprecedented access to molecular, clinical, and real-world data, as well as computational tools that allow systematic identification of new therapeutic uses. These approaches can move existing drugs into clinical use more efficiently, broaden therapeutic options, and improve patient access. When the repurposing opportunity involves a generic medication, access may be further expanded if the drug is already widely available and low-cost.

Yet significant challenges remain. Even when compelling evidence exists, repurposed drugs often face barriers to adoption. Generic drugs typically lack commercial incentives for companies to fund large-scale confirmatory trials or support regulatory submissions for new indications. As a result, many promising repurposing opportunities stall before reaching patients. Beyond regulatory hurdles, the integration of repurposed therapies into clinical guidelines and pathways requires broad awareness.

Looking forward, the field of drug repurposing will need to balance the potential for rapid discovery with practical strategies for delivery, regulatory approval, and clinical adoption. Reboot Rx’s mission is to address these challenges and advance promising discoveries through research, policy, and education. Through this work, we aim to ensure that repurposed drugs achieve meaningful clinical impact and provide a practical, cost-conscious path to meet evolving therapeutic needs.